NCAI History

Table of Contents

- Seventy Years of NCAI: From Imminent Threat to Self-Determination

- NCAI Founding Principles:

- From Imminent Threat to Self-Determination

- 1940's

- 1950's

- 1960's

- 1970's

- 1980's

- 1990's

- 2000's

- 2010's

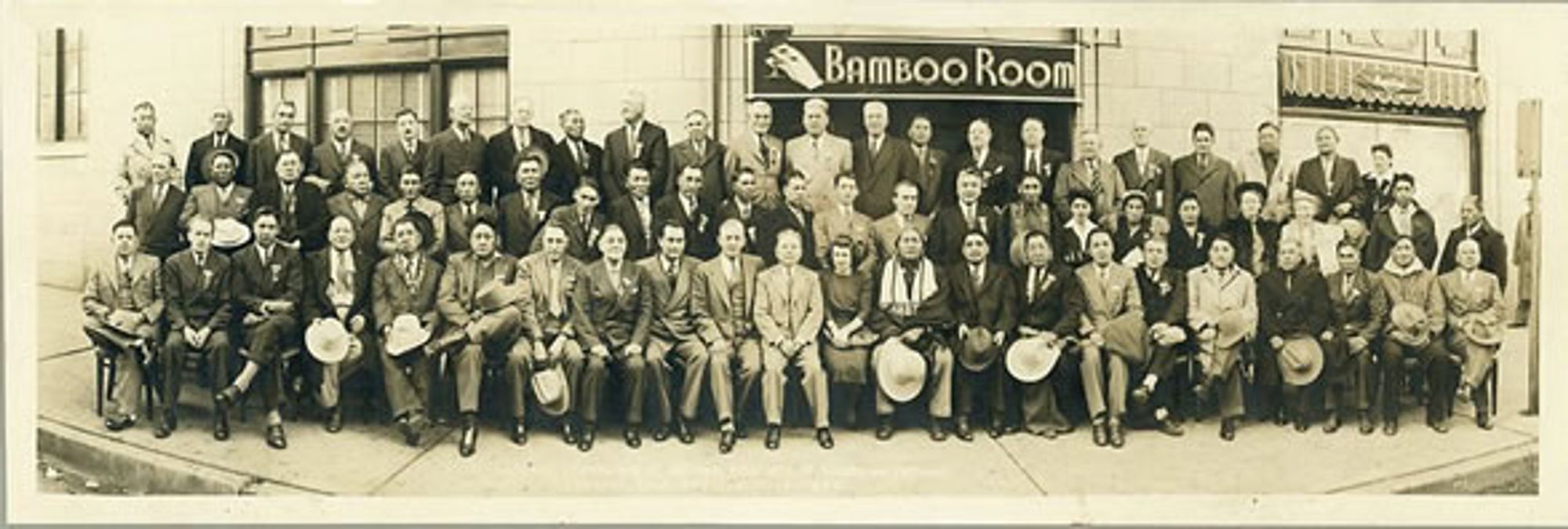

National Congress of American Indians charter Members at the Constitutional Convention Cosmopolitan Hotel, Denver, Colorado, November 15-18, 1944

Download a full list of members in the photo.

NCAI was established in 1944 in response to the termination and assimilation policies the US government forced upon tribal governments in contradiction of their treaty rights and status as sovereign nations. To this day, protecting these inherent and legal rights remains the primary focus of NCAI.

NCAI Mission

Protect and enhance treaty and sovereign rights.

Secure our traditional laws, cultures, and ways of life for our descendants.

Promote a common understanding of the rightful place of tribes in the family of American governments.

Improve the quality of life for Native communities and peoples.

NCAI History

In Denver, Colorado, in 1944, close to 80 delegates from 50 tribes and associations in 27 states came together to establish the National Congress of American Indians at the Constitutional Convention. Founded in response to the emerging threat of termination, the founding members stressed the need for unity and cooperation among tribal governments and people for the security and protection of treaty and sovereign rights. The Founders also committed to the betterment of the quality of life of Native people.

Read about the First Constitutional Convention of NCAI.

Seventy Years of NCAI: From Imminent Threat to Self-Determination

From 1944 to the modern era of government relations between tribal governments and US governments, NCAI has been a leading force and voice in protecting tribal sovereignty.

Read a brief history of NCAI’s historic and modern role in protecting tribal sovereignty.

NCAI Founding Principles:

To secure and preserve American Indian and Alaska Native sovereign rights under treaties and agreements with the United States, as well as under federal statutes, case law, and administration decisions and rulings.

To protect American Indian and Alaska Native traditional, cultural, and religious rights.

To seek appropriate, equitable, and beneficial services and programs for American Indian and Alaska Native governments and people.

To promote the common welfare and enhance the quality of life of American Indian and Alaska Native people.

To educate the general public regarding American Indian and Alaska Native governments, people, and rights.

From Imminent Threat to Self-Determination

Over the course of the 225 years since the recognition of the inherent sovereignty of “Indian tribes” in the US Constitution—listed alongside foreign nations and state governments (see Commerce Clause)—the unique place of tribal nations as members of the American family of governments has been gravely misunderstood. In spite of the promise offered by tribal nations, too many times this governmental status has been completely disregarded and legally violated.

And yet today, as a result of relentless and unified efforts by tribal governments and Native peoples, tribal nations stand stronger now than ever. Collectively these efforts reversed the course of termination, manifested the self-determination era, and continue to hold the US government accountable in its federal trust responsibility to tribal nations.

These efforts began early in the 20th century—nearly 70 years ago—when tribal governments, leaders, and citizens came together to forge a powerful coalition to secure their rights and status. In that moment, during the founding of NCAI, tribal governments formally promised to never relinquish their inherent sovereignty as America’s first governments.

Throughout modern history, NCAI has served as the unified force to protect against regular attempts, both unintentional and deliberate, to ignore treaties between tribes and the US government, overlook the US Constitution, undermine federal legal precedent, and dilute the intrinsic sovereign rights of tribal nations.

The brief snapshot of the history of NCAI up until today, which follows below, is an inspirational story of cultural and political perseverance, the foundation for a hopeful future for Native people, and a lesson in the power of tribal governance and tribally driven policy advocacy. It has inspired our Indigenous brothers and sisters around the world.

The following is a general history of the last seventy years of NCAI and the policy efforts of our members to protect tribal sovereignty for all Native people and tribal nations.

1940's

In the early 1940s, members of Congress and factions in the federal government began to amass an effort in what historians point to as the beginning of an era—the termination era. The termination era, – the attempt to completely terminate federally recognized tribes, became the greatest threat to tribal sovereignty in the 20th century.

In response to this imminent threat of termination, nearly 80 delegates from 50 tribes and associations in 27 states came together in Denver, Colorado, in 1944 to establish the National Congress of American Indians. By the following year, membership had risen to more than 300, claiming members from nearly every tribe in the United States.

Among the first acts of NCAI was to file successful lawsuits in Arizona and New Mexico to press for Indian voting rights, firmly establishing a theme of Native political participation. Read more about the meeting and the proceedings of the event.

1950's

In February 1954, NCAI called an emergency conference on the termination of Indian tribes in the United States, marking a turning point in slowing and stopping the coercive termination program. More than 4,000 newspapers and numerous radio/TV stations covered the event, including the BBC. At the November 1954 annual session, NCAI proposed a Point IX program as an alternative to the forced termination legislation. The proposal laid out a technical assistance program for long-term self-sufficiency. NCAI fought for Indians’ unrestricted choice of legal counsel, crucial to Indian civil rights and self-determination in the early ‘50s.

1960's

In 1961, NCAI helped plan the American Indian Chicago Conference, the largest inter-tribal gathering in decades, spurring public interest in Native policy. The conference resulted in a “Declaration of Indian Purpose,” a statement of concerns and recommendations with an emphasis on tribal sovereignty and preserving American Indian and Alaska Native identity. This statement was delivered to President Kennedy in the White House, and later in the 1960s, many of these proposals were implemented with tribal specific policies included in Johnson’s “Great Society” programs.

1970's

In his July 1970 Presidential Statement, Nixon called for an end to termination as a policy and provided a clear and direct Presidential endorsement of a self-determination policy for the first time. With support and advocacy from NCAI, in 1975, the policy was given permanence as Public Law 638, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. With significant advocacy work from NCAI, passage of the Indian Health Care Improvement act in 1976, as well as the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978, further underscored a new era of respect for tribal control over their own destinies and lifeways and a commitment to fulfilling the trust responsibility.

1980's

In 1983, President Reagan issued an Indian Policy Statement signaling that the Administration’s belief in local control applied to tribal governments, alongside their state government peers. Reagan’s policy statement reaffirmed the Administration’s intent to deal with tribes on a government-to-government basis and underscored a maturing policy of self-government for tribes without threat of termination. NCAI stood at the forefront in the environmental arena as tribes increasingly sought control of environmental protection and resource management. Passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory act in 1988 ushered in a new era of opportunity and challenge for tribes.

1990's

In the wake of the 1990 Supreme Court decision in Duro v. Reina, which held that tribes did not possess criminal jurisdiction over non-member Indians, NCAI pushed successfully for passage of a “Duro Fix” which affirmed and recognized tribes’ inherent right to exercise criminal jurisdiction over Indians. With input from NCAI, President Clinton issued a memorandum to all Executive Departments in 1994 outlining Departmental responsibilities to consult with tribal governments in a government-to-government relationship.

2000's

In 2000, President Clinton signed an Executive Order on Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments, reaffirming the US Government’s responsibility for continued collaboration and consultation with tribal governments in the development of federal policies that have tribal implications. Tribes came together beginning in 2001 in a coordinated effort to address recent Supreme Court decisions that demonstrated an accelerating trend toward diminishing tribal jurisdiction on their lands. NCAI expanded the programmatic work of the national office, launching the Tribal Sovereignty Protection Initiative, the NCAI Policy Research Center, and the Native Vote campaign.

During the Presidential campaign of now-President Barack Obama, he committed to hosting an annual White House summit with tribal nations and appointing a Native American Policy Advisor on his senior staff. The fulfillment of these commitments raised the level of nation-to-nation engagement and expanded tribal consultation across federal agencies. At the 2009 Summit, President Obama issued an Executive Memorandum, reinforcing the policies of President Clinton’s Executive Order on Consultation and directing all agencies to develop and submit implementation plans. A long-time dream for Indian Country was fulfilled in November 2009 when the Embassy of Tribal Nations was formally opened as a permanent home base for tribal nations in the US capital, a physical and powerful reminder of the nation-to-nation relationship

2010's

In 2010, landmark tribal policy priorities were enacted into law, including the historic Cobell settlement, the Tribal Law & Order Act, and the Indian Health Care Improvement Act. At the December 2010 White House Tribal Nations Summit, President Obama announced the federal government’s endorsement of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This announcement paralleled NCAI’s expanded role in collaboration with Indigenous peoples around the world. In 2011, NCAI provided a keynote address at the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and hosted an historic joint board meeting with the Assembly of First Nations (Canada).