VAW Resource Center

The Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010

The Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010 (TLOA) is a law signed into effect by President Barack Obama that expands the punitive abilities of tribal courts across the nation. This law allows tribal courts operating in Indian Country to increase jail sentences handed down in criminal cases over Indian offenders.

The purposes of the Tribal Law and Order Act are to:

Clarify the responsibilities of the federal, state, tribal, and local governments regarding crimes in Indian Country;

Increase coordination and communication among federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement agencies;

Empower tribal governments with the authority, resources, and information necessary to safely and effectively provide public safety in Indian Country;

Reduce the prevalence of violent crime in Indian Country and combat sexual and domestic violence against Alaska Native and Native American women;

Prevent drug trafficking and reduce rates of alcohol and drug addiction in Indian Country; and

Increase and standardize the collection of criminal data and the sharing of criminal history information among federal, state, tribal, and local officials responsible for responding to and investigating crimes in Indian Country.

If a Tribal Nation meets specific requirements that ensure the protection of defendants, then their maximum sentencing is increased to three years in jail per offense (with stacking of offenses up to nine years per criminal proceeding) and/or $15,000 per offense.

Prior to the passage of the TLOA, the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) severely limited the sentences that a Tribal Nation could impose on offenders. Under ICRA, the maximum sentence for convicted felonies is one year of imprisonment and a $5,000 fine. Other penalties such as community service, restitution, and exclusion are not limited under ICRA. Nevertheless, the ICRA severely hampered the ability of Tribal Nations to respond to serious and repeat offenders. The TLOA was a major step toward improving enforcement and justice in Indian Country—and a precursor to the 2013 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA).

Background: The Indian Civil Rights Act

The Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) guarantees due process to all defendants in tribal court. The rights guaranteed by ICRA include:

The right not to be deprived of liberty or property without due process of law.

The right to the equal protection of the tribe’s laws.

The right against unreasonable search and seizure.

The right not to be twice put in jeopardy for the same tribal offense.

The right not to be compelled to testify against oneself in a criminal case.

The right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation in a criminal case.

The right to be confronted with adverse witnesses.

The right to compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in one’s favor.

The right to have the assistance of defense counsel.

The right to effective assistance of counsel at least equal to that guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

The right of an indigent defendant to the assistance of a licensed defense attorney at the tribe’s expense.

The right to be tried before a judge with sufficient legal training who is licensed to practice law.

The right against excessive bail, excessive fines, and cruel and unusual punishment.

The right to access the tribe’s criminal laws, rules of evidence, and rules of criminal procedure.

The right to an audio or other recording of the trial proceedings and a record of other criminal proceedings.

The right to petition a federal court for a writ of habeas corpus, to challenge the legality of one’s detention by the tribe.

The right to petition a federal court to be released pending resolution of the habeas corpus petition.

TLOA and VAWA Due Process Requirements

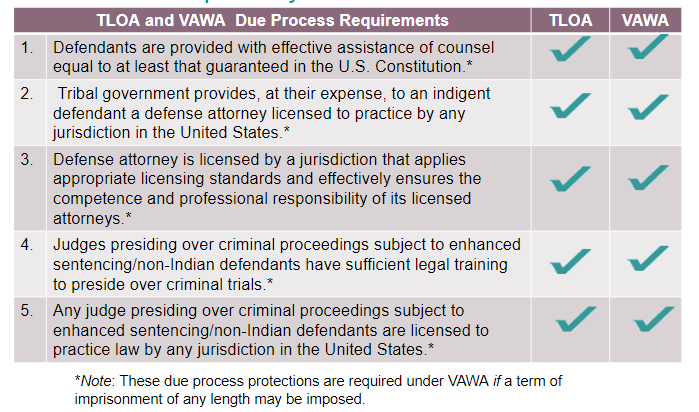

As sovereign nations, Tribal Nations are not required to adopt and operate under the TLOA. Likewise, exercising special tribal criminal jurisdiction (STCJ) under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) is entirely voluntary and elective for Tribal Nations. However, if a Tribal Nation decides to exercise the enhanced sentencing provisions provided by the TLOA, its tribal justice systems must meet certain requirements. The following due process protections are required under the TLOA. They are only required under VAWA if a term of imprisonment of any length may be imposed:

Effective assistance of counsel equal to what would be available in federal or state court /is equal to that guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution;

Free, appointed, and licensed attorneys for indigent defendants;

Law-trained tribal judges who are licensed to practice law in any jurisdiction in the United States;

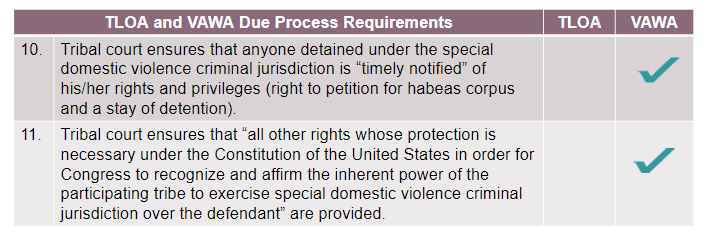

Publicly available tribal criminal laws and rules of evidence and criminal procedure; and

Maintain a record of criminal proceedings, including audio or video recordings of trial proceedings.

Many of the requirements of the TLOA and VAWA overlap. However, a Tribal Nation may choose to exercise the authority recognized in one statute but not another. If a Tribal Nation chooses to exercise STCJ, they must meet the following requirements of VAWA:

Tribal courts must provide the right to a trial by an impartial jury that is:

Drawn from sources that reflect a fair cross-section of the community; and

Does not systematically exclude any distinctive group, including non-Indians.

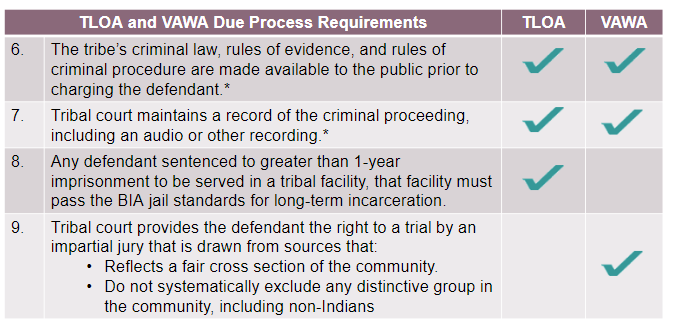

Tribal courts must ensure defendants are timely notified of the right to habeas corpus and their right to petition for a stay of detention.

Although both the TLOA and the VAWA expand the ability of Tribal Nations to keep their communities safe, there are many reasons why tribal leaders might choose not to implement the TLOA, VAWA, or both. Some tribes would like to implement these new standards but lack the resources and qualified personnel to meet the due process requirements. Others might prefer not to update their tribal codes to reflect the changes necessitated by these statutes. Finally, some Tribal Nations might simply not want to implement the codes and prefer to exercise their sovereign right not to do so. For example, some Tribal Nations have decided not to adopt the TLOA for fear of exposing their tribal members to enhanced sentencing provisions.

The following graphic is designed to help clarify the relationship between the TLOA and VAWA due process requirements.

The TLOA amended the ICRA to permit enhanced sentencing in two significant ways. First, when a defendant is a repeat offender previously convicted of the same offense or a “comparable offense” in any jurisdiction, and, second, if the defendant is convicted in tribal court of an offense that would be comparable to one punishable by more than one year of imprisonment if prosecuted in federal or state court.

Tribal Nations Exercising the Enhanced Sentence Provisions of TLOA, but not VAWA STCJ:

Hopi Tribe.

Tribal Nations that exercise VAWA STCJ and not TLOA are:

Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians

Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

Sac and Fox Nation

Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma

Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa

Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa & Chippewa Indians

Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation

Pueblo of Santa Clara

Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

Quapaw Tribe

Penobscot Nation

Resources:

ILOC Report: A Roadmap For Making Native America Safer: The Indian Law and Order Commission released its final report and recommendations—A Roadmap For Making Native America Safer—as required by the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010. This report reflects one of the most comprehensive assessments ever undertaken of criminal justice systems servicing Native American and Alaska Native communities. Review the Executive Summary.

U.S. Department of Justice Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions Report: Published annually, the most recent report was published in 2021 and can be found at the U.S. Department of Justice Website.

Tribal Law and Order Act: Enhanced Sentencing Authority: Provided by the Tribal Justice Institute, the Tribal Civil and Legal Criminal Assistance Program and the Bureau of Justice Assistance, this Tribal Code Development Considerations Quick-Reference Overview & Checklist is a useful resource for implementation.

Tribal Legal Code Resource: Tribal Laws Implementing TLOA Enhanced Sentencing and VAWA Enhanced Jurisdiction: Designed to be a resource for tribes interested in implementing the Tribal Law and Order Act sentencing enhancement provisions or VAWA 2013’s Special Criminal Domestic Violence Jurisdiction. The resource focuses on the tribal code and rule changes that may be needed should a tribe elect to implement the increased tribal authority in either or both statutes. It discusses the concerns and issues that need resolution in implementation and provides examples from tribal codes and court rules.